Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) based on vanilla Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) are widely believed to be incapable of representing high-frequency content. This has directed research efforts towards architectural inter- ventions, such as coordinate embeddings or specialized activation functions.

In this paper, we challenge the notion that the low-frequency bias of vanilla MLPs is an intrinsic, architectural limitation, but instead a symptom of stable rank degradation during training. We empirically demonstrate that regulating the network's rank during training substantially improves the fidelity of the learned signal, rendering even simple MLP architectures expressive.

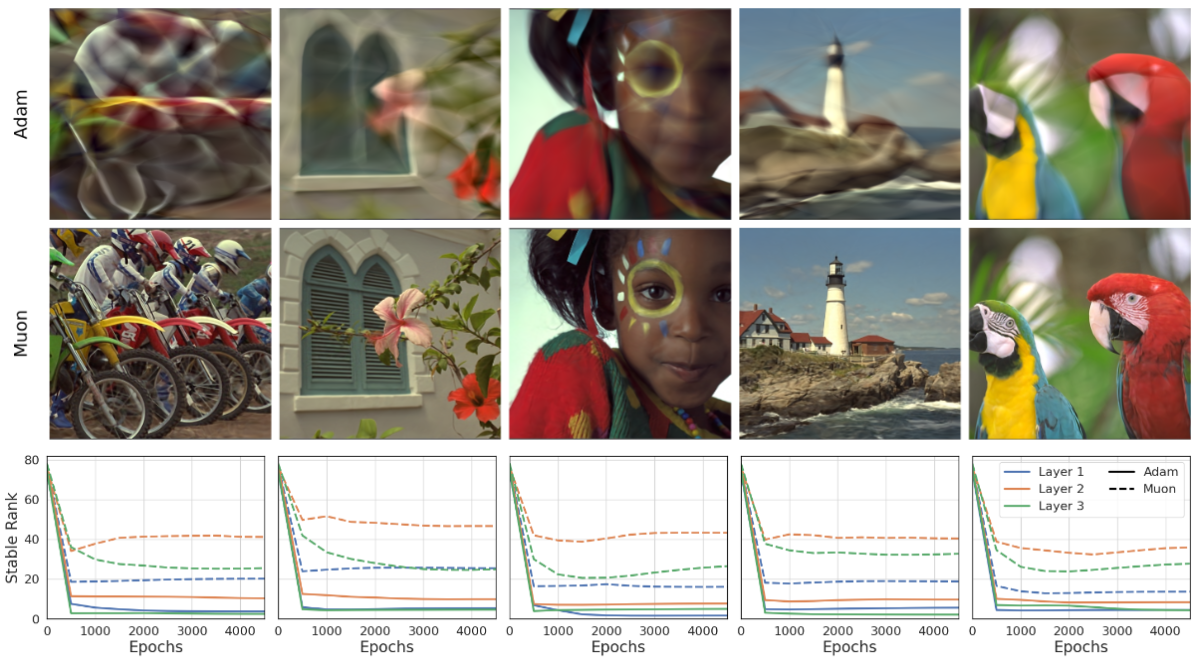

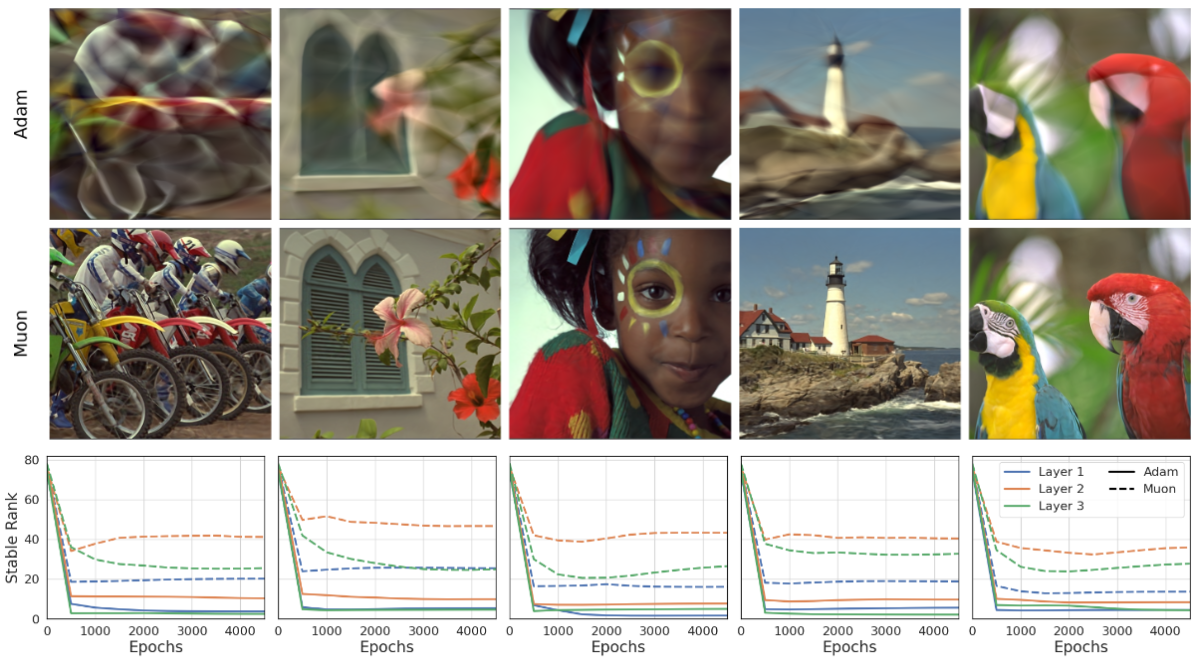

Extensive experiments show that using optimizers like Muon, with high-rank, near-orthogonal updates, con- sistently enhances INR architectures even beyond simple ReLU MLPs. These substantial improvements hold across a diverse range of domains, including natural and medical images, and novel view synthesis, with up to 9 dB PSNR improvements over the previous state-of-the-art.

The phenomenon of spectral bias describes how neural networks prioritize low-frequency functions during training. Rather than analyzing this in the function's Fourier spectrum, we examine how it arises from the linear-algebraic structure linking activations and weights through gradients. Based on the stable rank of layer updates, we clarify how activations shape layer weights, why this reinforces a low-frequency bias in INRs, and how different interventions address this bias.

To quantify the effective dimensionality of this process, we use the stable rank \(s(A)\) as a numerically stable measure of diversity for a matrix \(A\) with singular values \(\sigma_{i}\):

$$ s(A) = \frac{\|A\|_F^2}{\|A\|_2^2} = \frac{\sum_i \sigma_i^2}{\sigma_{\max}^2} $$A rank-1 matrix has \(s(A)=1\), while a semi-orthogonal matrix with rank \(k\) has \(s(A)=k\). Applying this inequality to the batched gradient \(\nabla_{W_{l}}\mathcal{L}=G_{l+1}H_{l}^{\top}\) gives:

$$ s(\nabla_{W_{l}}\mathcal{L}) \le \text{rank}(H_{l}) $$Thus, for a single layer, it is crucial to understand that the input activations constrain the effective dimensionality of the update and consequently its capacity to explore the layer's weight space.

Based on this insight, we provide a unifying framework that explains the effectiveness of common architectural modifications in INRs. We group these interventions into broad categories of architectural modifications.

Methods such as Fourier Features map the low-dimensional input coordinate \(x\) to a high-dimensional vector \(\gamma(x)\) using sampled random frequencies.

A direct approach targets the activations themselves to counter rank diminishing with depth.

We instead view this challenge as an optimization problem, calling for direct intervention at the update level.

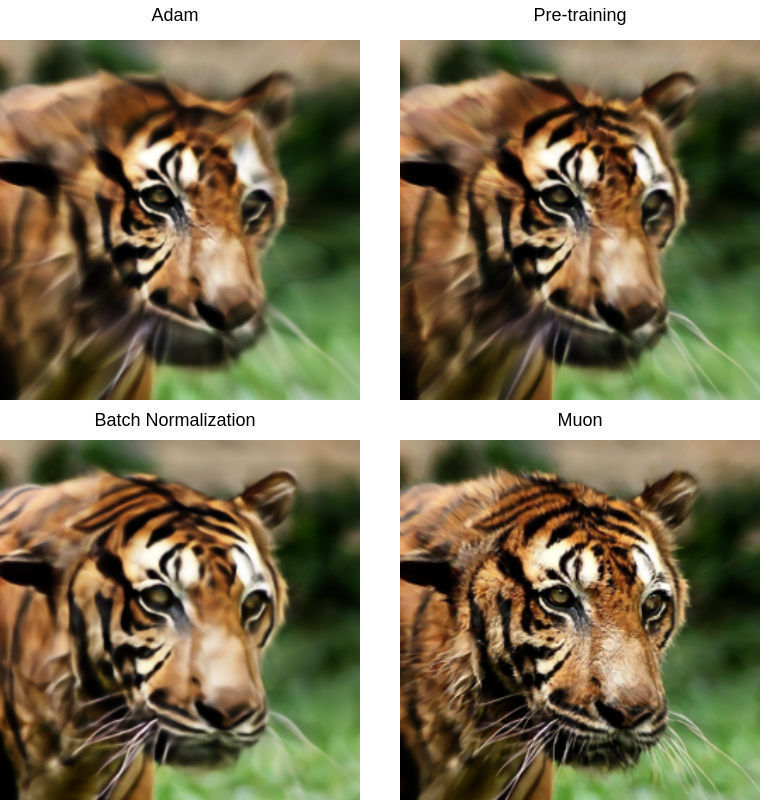

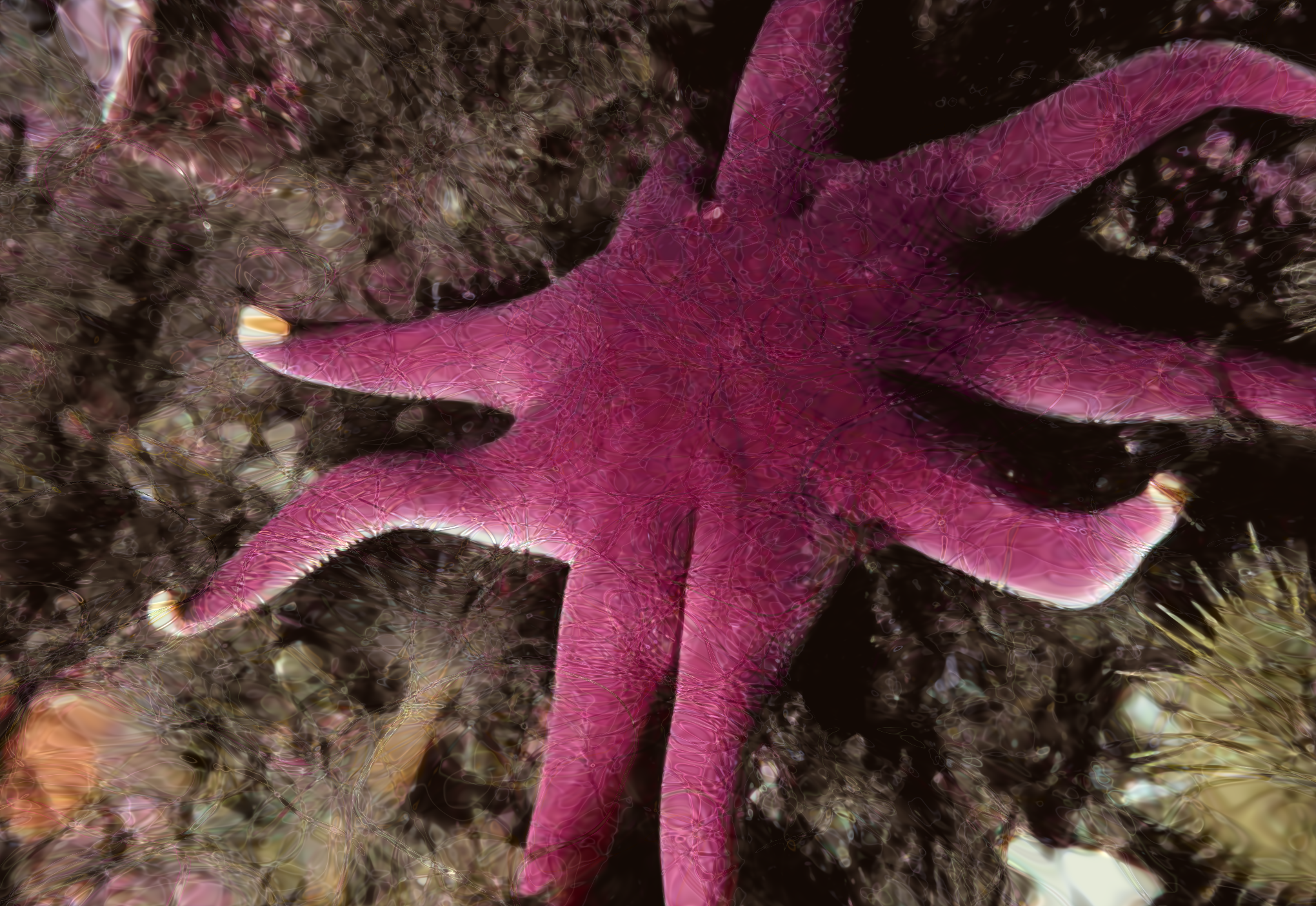

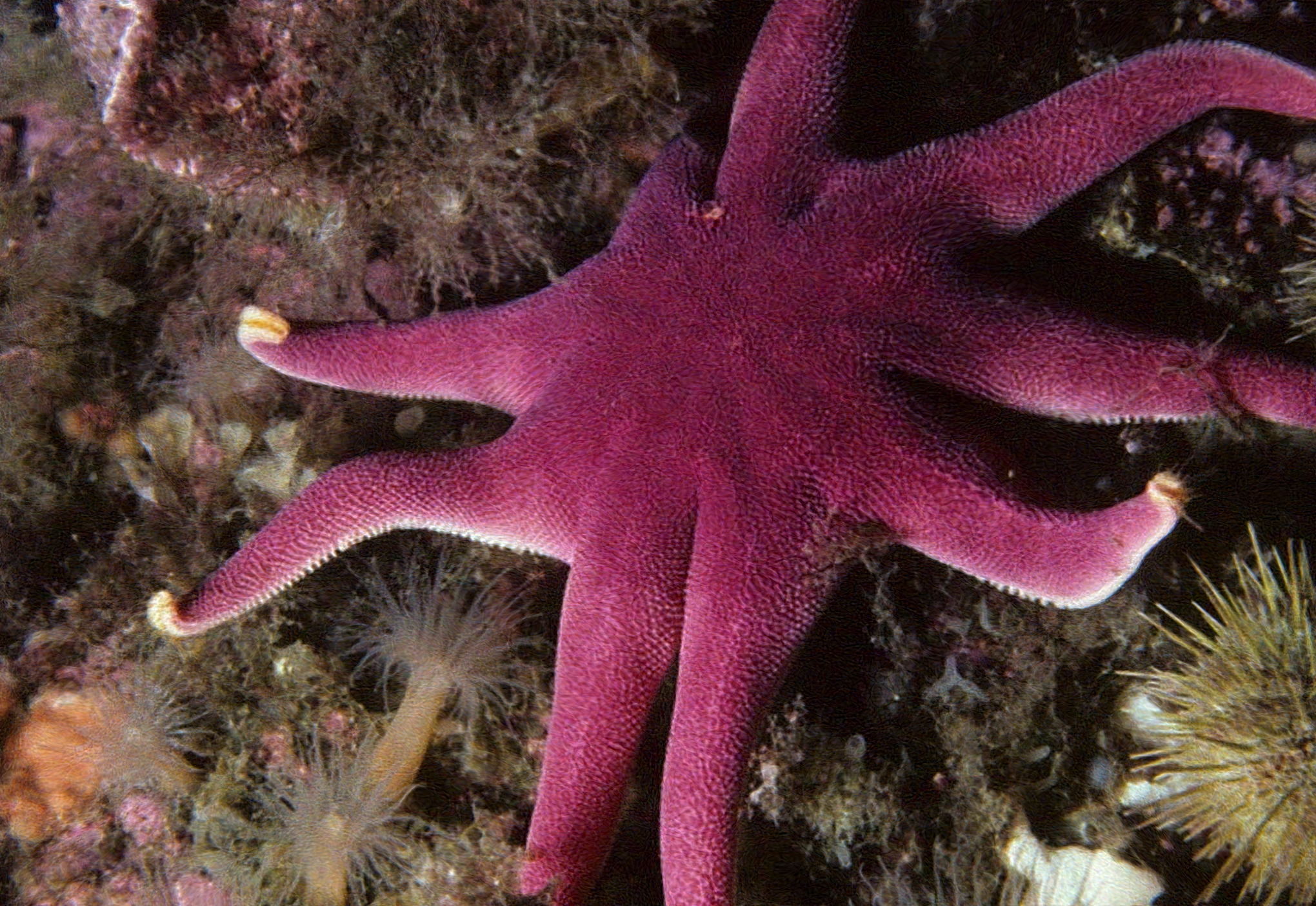

Reconstructing a tiger from the animal AFHQ dataset using a vanilla ReLU MLP and different rank-preserving/inducing methods. We propose to use Muon, which induces a high stable rank via its orthogonalized weight updates.

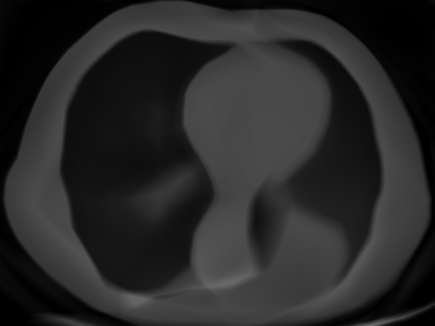

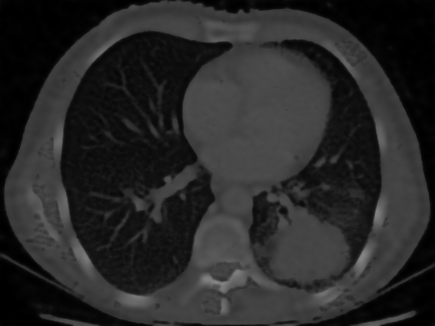

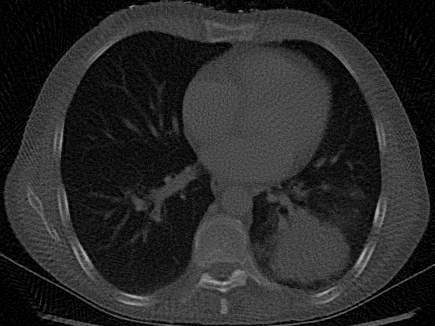

We reconstruct a chest CT from only 100 sparse projections. Optimization with Muon significantly reduces streak artifacts and recovers fine anatomical structures (such as bronchi) compared to Adam.

We compare the reconstruction fidelity of various implicit architectures when optimized with Adam versus Muon. Drag the slider to observe how rank-preserving optimization recovers high-frequency details (e.g., textures, edges) that are smoothed out by Adam.

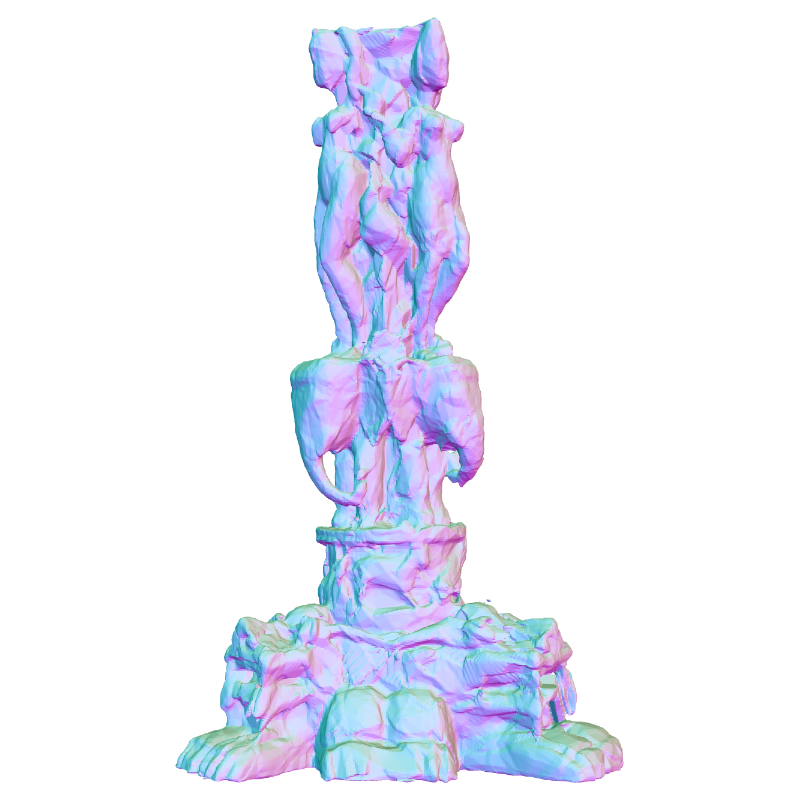

We compare the reconstruction of 3D signed distance fields (SDFs) using a standard ReLU MLP. Muon captures sharp geometric features that are smoothed by Adam.

Comparisons on the Chair scene. Muon (right video in each pair) produces sharper, more geometrically consistent renderings with fewer "cloudy" artifacts than Adam.

Comparisons on the Drums scene. Similarly, Muon demonstrates superior high-frequency detail reconstruction and geometry compared to Adam.

@misc{mcginnis2025optimizing,

title={Optimizing Rank for High-Fidelity Implicit Neural Representations},

author={Julian McGinnis and Florian A. Hölzl and Suprosanna Shit and Florentin Bieder and Paul Friedrich and Mark Mühlau and Björn Menze and Daniel Rueckert and Benedikt Wiestler},

year={2025},

eprint={2512.14366},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CV},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.14366},

}

This work is funded by the Munich Center for Machine Learning. Julian McGinnis and Mark Mühlau are supported by Bavarian State Ministry for Science and Art (Collaborative Bilateral Research Program Bavaria – Quebec: AI in medicine, grant F.4-V0134.K5.1/86/34). Suprosanna Shit is supported by the UZH Postdoc Grant (K-74851-03-01). Suprosanna Shit and Björn Menze acknowledge support by the Helmut Horten Foundation.